The Life After

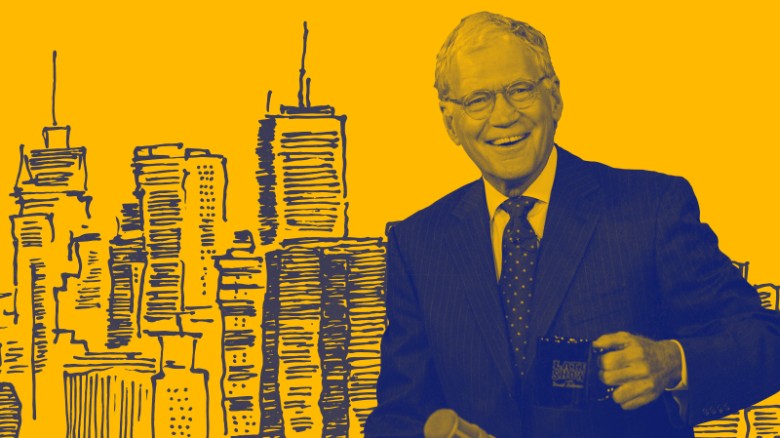

I knew it was going to be bad for me when David Letterman retired, but I didn’t know it was going to be this bad.

The first week, I pretended that he was on vacation—he did go on a lot of vacations. Not that he didn’t deserve them. He worked so much and for so long and wanted things to be perfect. He hated mistakes. I once saw him hold up a small card with a little blue piece of paper taped to it. The card was something like an index card. He was reading from the paper on the card. Maybe it was during a Fun Fact segment. And then he saw on the monitor that the blue paper had a little tear at the top of it and had been Scotch-taped together onto the card. “What’s this!” he said, with some anger—he was more than annoyed. “Torn and taped to the card!” He shook his head. Or maybe he said, “What kind of Mickey Mouse show is this?” Maybe he said both. I can’t remember exactly which way he said it. I just remember how he shook his head with disgust, and that he was angry.

That’s one of the things I liked best about him. He’d show how disgusted he was with something going wrong on the show or with something someone said on the show. The most shocking example of this kind of behavior follows: I saw him talking to a Hollywood actor on another program. They were both standing up. This was during the era when men wore sports jackets with the sleeves pushed up. There have been worse things to see in style in the next decades, but that one stays in the mind. He walked a couple of steps toward the actor and grabbed at the sleeves and pulled them down. The Hollywood actor looked surprised. I think he was one of those good-natured Hollywood actors and didn’t understand the whole thing. He didn’t understand disgust with Hollywood ways.

I found the style ridiculous and repellant, too, but I never thought anyone would make a move as hostile and amusing as pulling those sleeves down on another person, on TV. You could like Dave for this and fear him at the same time. That was one of the most unusual things I’ve ever seen on television—the pulling down of those sleeves. This was many years before Dave learned how to meditate, calm down, and deal with his hostility.

But now what are we supposed to do? He shouldn’t have been allowed to retire. It was a job, like being President. His term wasn’t over. In any case, David Letterman is more important than any President and has accomplished more than most of them—he made people laugh.

They should have let him work November through March—three shows a week. Then he could have had the good-weather months free. He once said that he didn’t mind being in New York when it rained. But when it was good weather he liked to be out of the city, in the country.

Now things are bleak. There’s nothing funny to look forward to. There’s just emptiness and darkness and quiet, without David Letterman.

And I know I’m not the only one. A few people called me. There was one person—I was afraid she was going to call. But I didn’t have my glasses on, and I didn’t see the caller I.D., so I made the mistake of answering the phone. And I said, “Oh no, I was afraid you were going to call about this. I just can’t talk about it. It’s caused a deep depression.”

On the other hand, I’m not like the woman who sneaked into Dave’s house several times and eventually committed suicide on a train track. Although I’m married, my husband doesn’t talk. So I depended on David Letterman to talk. In the beginning, these programs were all called talk shows. Every night, I could calm down before trying to go to sleep. I rarely watched the Hollywood-actor parts. Or the sports part—other than Marv Albert’s Bloopers segment.

Dave is complex, he’s complicated, and, now that he’s calmed down, he’s a changed person. He attributes it to meditation. He has a meditation teacher he refers to as “Meditation Bob,” who teaches the supposedly most important people. I can’t get Meditation Bob to teach me. I guess I have to remain crazed with anxiety. Once, on the show, I heard Dave say he wanted to learn how to meditate, but he didn’t want some guy coming into his house and taking his shoes off. Did he want people coming into his house with their shoes on, with the bacteria and dirt from everywhere in the world on their shoes? The shoes have been in airports.

I don’t know how I’m going to calm down now that I don’t have his new calmness and funniness or wittiness spreading over and through to my brain.

It’s known that he was a private person. But sometimes you could see right underneath to how he felt. I’ve seen him start to cry, I’ve seen him almost cry, I’ve seen him cry. I’ve seen him looking sad underneath the smiling. I know the kind of thing he’s thinking about. And when they said that his last show was happy, not sad, they were wrong. All that joviality and fun—there was so much sadness underneath. He was trying so hard to make it happy, it made it even sadder.

But who knows? Maybe he went home and cried all night. I mean, after he got his son to bed. Maybe he’s been crying all year. Maybe he’s still crying. I read that he went off and had some fun, some racing-car thing that he likes to do—I never watch that part of the show. I don’t understand these sports things. I don’t understand the Indy 500. I don’t even know what it is. I overlooked that particular one of his interests.

I don’t understand why Dave had Martha Stewart on so often. Last year, when she was on the show, he told her that he had Lyme disease. She said, “So what? I’ve had it, everyone has had it.” And he repeated, “I have Lyme disease!” He seemed alarmed. And she said, “I don’t care that you have Lyme disease.” She said it in a really mean, heartless tone of voice—and then I understood why a number of people don’t like her. She’s not just making peanut-butter-and-cherry sandwiches and planting herbs. I don’t even want to mention her name, the way Norm MacDonald said he didn’t want to dignify Hitler by saying his name—he said he didn’t want to give him the dignity or something like that. Then, at the end of the show, he told David Letterman he loved him, and Norm MacDonald started to cry.*

And then there’s the Johnny Carson thing. I never understood why Dave idolized him. The best thing I ever saw on Johnny Carson—I know he was witty; still, it wasn’t the kind of show I wanted to watch—was once when Shelley Winters was on as a guest, and she talked about her daughter who went to Harvard and was getting an advanced degree in something important. Then she stopped and said, “Oh, but you wouldn’t know about that.” And he looked at her, without any kind of meanness—he looked completely innocent—and he said, “Why not? I went to college.” And everybody laughed. Maybe Shelley Winters didn’t laugh.

When he worked at NBC, Dave went to introduce himself to the president of that corporation, outside on the street—he filmed this—and he put out his hand to shake hands with this executive of NBC, and the executive wouldn’t shake hands with him. The crew filmed all of that, the moving away from the proffered hand. He would often have it shown in slow motion while playing the NBC chimes at the same time. Original. Unique. Funny and absurd.

There’s a man I knew from our town. He was a chain-smoker. Every time I met him outside at night, he’d light up. I’d say, “If you want to talk to me, you can’t smoke.” I once said, “Anyway, I have to go home and watch David Letterman.”

And the smoker surprised me by saying, with some bitterness, “You and every other arty, intellectual chick in the world.” I didn’t know which was more surprising—the part about being called an arty, intellectual chick, or that the arty chicks had to watch David Letterman. I guess the smoker had many failed experiences of trying to seduce women who would rather watch Dave’s show.

Why did all the “arty chicks” have to watch Dave? He wasn’t the usual sort of heartthrob. Not that he didn’t look good—he looked really good. He had unique hands and wrists. And there were little blond hairs on the top of his hands and wrists. That must drive women crazy.

During the last few years, when he had less hair on his head, it wasn’t always neat. It looked as if he combed it himself and gave up. Once, last year, he said, “Someone wrote an Op-Ed piece in the New York Times about how ugly my hair is.” I tried to Google that, but I could never find it.

Every night, a feeling of nothingness and emptiness comes over me. When I look at the clock, I see that it’s midnight, and I realize I haven’t watched Dave. I remember what’s missing.

One night, I found I was watching what I thought was a science-fiction movie about giant killer ants. It was from the nineteen-fifties. The title was “Them!” When I looked it up a few days later, on IMDb, I saw the words “genre—horror.” Had I known it was horror, not science fiction, I wouldn’t have watched it.

This ant movie is about giant killer ants, twice or three times as big as a man. They’ve taken over a small New Mexico desert town where there’s atomic radiation, where atomic-bomb experiments were probably carried out. So they’re giant mutant killer ants. And what they do is put their giant pincers around a man. But, first, a loud crackling sound is heard. That’s the sound that they’re coming to get people. And then they put these giant pincers, which I looked up in ant anatomy—they’re just called feelers there on Google—they put the pincers around a man. The whole ant-anatomy drawing made me feel sick. I tried to keep looking at the drawing to understand the name they used for the pincers in the movie. I had to give up. But I kept watching the movie because I like to see how people spoke and dressed in movies from the nineteen-fifties. Many were smoking most of the time. I didn’t really care about the ant plot. I figured it would have a happy ending. It was disappointing when James Whitmore’s character, a local official in charge of killing the last two queen ants of the colony, is attacked by one and is strangled or poisoned. It appeared to be a fatal attack.

By then I was taping the movie, but I’d already taken a one-milligram sublingual melatonin tablet and didn’t have the enthusiasm or energy to replay the dialogue. The James Whitmore character was just lying there, in the pitch-dark ant cave, so I just figured I’ll assume he’s dead until I play it again.

Then I realized I had watched this movie, “Them!,” instead of Dave, and that’s why I felt so bad. And I felt bad for days after, thinking of those giant, black killer ants.

And to think, when we were very young, and Dave was the guest host on Johnny Carson’s show, I’d say, “Oh no, not him. Let’s watch something else.”

When I asked my agent, “What am I going to do now?,” this is what he said, in an uncaring way: “So you’ll watch the other guy.” And I said, “It’s not a question of the other guy.” Stephen Colbert is a whole other kind of guy. It’s just too nerve-wracking. It’s not like being talked to by Dave.

In the early days of Stephen Colbert’s show, he was interviewing a congresswoman, Carolyn Kilpatrick, and he said, “May I call you Carolyn?” And she said no, she preferred to be called Congresswoman. And he said, “Yes, Carolyn, I have a quote from . . .” I remembered, at the time, that I laughed, and I hadn’t laughed in a long time. I remember the look on her face. She looked at him as if he were a madman.

The agent wasn’t interested in the Dave situation—he was in a hurry to go do something to make more money than he would by talking to me about this topic. And he quickly got off the phone.

Which are worse—lawyers, agents in all professions, or doctors these days? I often hear people ask that. One thing that I loved about Dave was that he referred to agents, lawyers, and others in show business, especially in the music business, as weasels. It’s a whole world of weasels now.

The night after the ant movie, I saw that “The Stranger” was on Turner Classics. And this is one of my favorite movies in the world. I realized I had missed the first ten minutes. I had tuned in at the part where a frail old-man Nazi comes to the idyllic New England small town of Harper, Connecticut, to find and give a Nazi message to the higher-up Nazi mastermind. I watched it even though I know it’s not like watching Dave. I didn’t want to go to sleep, because I realized that I hadn’t done one fun thing the entire day. And I didn’t have David Letterman, the one fun thing to watch before trying to fall asleep. I took my first dose of three 2.5-milligram melatonin tablets. That just calms you down and gets you ready for the next sleep-inducing dose. So I figured I would be able to watch the whole movie, especially since I know it by heart.

In the end—I know it’s not an unhappy ending, but it is a gruesome ending—Loretta Young has had a nervous breakdown because she’s found out that she’s married a man without knowing he was a Nazi mastermind who was behind the worst atrocities. There’s no new love on the horizon for her. Cary Grant would have been just right, but he’s not even in the movie. It’s not clear what her future will be, rushing out at night to shoot and kill her Nazi husband in the church tower, dressed in her ankle-length, flowing and fluttering chiffon nightgown underneath a shoulder-padded three-quarter-length fur coat. I always wish I had that gown and coat, but in faux fur, and I hoped hers was faux fur, too.

It’s hard to imagine why she would marry Orson Welles—she’s so beautiful and is Judge Longstreet’s daughter, Mary Longstreet, from the first family of the idyllic New England town. Anyway, she’s just seen her Nazi husband stabbed through the heart with the sharp metal sword of a statue of a medieval person while he’s on the rotating clock-tower wheel he’s been working on.

The last part has Edward G. Robinson, playing Mr. Wilson, the government agent who tracked down the Nazi mastermind, Franz Kindler, tipping his hat and saying to Loretta Young, “Pleasant dreams.” He has a little smile as he says it, this last sentence of the movie. But what’s so funny? I think they could have had a better ending. Maybe they struggled and argued over the editing of it. They probably cut the last, best line. In any case, that night I had one of my worst nightmares, not about that film but about my own life. I woke up at 5:45 and I tried for two hours to fall back asleep.

Because of the air-conditioning and air-cleaning-machine sounds, I didn’t realize that a large tree limb had fallen onto the side porch in a rainstorm during the night. All I cared about was staying asleep. As Dave said, during the last weeks of the show, “You know how you wake up in the middle of the night and start worrying about things?” Well, maybe he has less to worry about now, but maybe he doesn’t. From haircuts to insomnia to weasels to baking pies to anxiety, he understands the human condition. It’s not all fun.

Fonte [the newyorker]

L’arrivo di Netflix in Italia è il Big Bang di cinema e tv – di Federico Bagnoli Rossi -

Si è tenuta mercoledì 9 dicembre presso la sede dell’ANICA la presentazione del libroNetflix in Italia e il Big Bang di cinema e Tv.

Il saggio, scritto da Stefano Zuliani, analizza lo scenario di settore dell’industria audiovisiva all’arrivo in Italia di Netflix, la principale piattaforma mondiale di Subscription Video-On-Demand. Attraverso un dialogo con alcuni tra i più importanti professionisti dell’industria, Zuliani si interroga in particolare se l’ingresso di questo importante player avvenuto il 22 ottobre scorso permetterà al mercato digitale di “sbocciare” definitivamente e che impatto avrà sulla filiera tradizionale e nel rapporto con le televisioni. Su questo e altri quesiti ho già scritto recentemente un articolo nel quale ho sostenuto come l’arrivo di Netflix e l’auspicata affermazione della distribuzione digitale completeranno un eco-sistema audiovisivo in cui tutti i canali di sfruttamento potranno “convivere” e continuare a svilupparsi in maniera complementare.

Come sottolineato a più riprese durante la presentazione, l’incremento dell’offerta legale è una delle iniziative fondamentali da sostenere anche in risposta al problema della pirateria. L’offerta legale sta diventando sempre più ampia e competitiva. Molti sono i consumatori che già hanno usufruito e utilizzano con regolarità questi servizi, ma è necessario altro tempo affinché l’utilizzo delle piattaforme legali diventi un’abitudine. Ben vengano pertanto anche le iniziative di promozione e le campagne di informazione. La stessa Autorità per le Garanzie nelle Comunicazioni ha individuato come prioritario, a fianco dell’attività di Enforcement, l’incremento e la promozione dell’offerta legale.

In occasione dell’uscita del libro ho voluto fare alcune domande all’autore sul tema, che riporto qui di seguito e che forniscono ulteriori spunti di riflessione.

L’arrivo di Netflix porterà ad un’affermazione definitiva della distribuzione digitale dei contenuti, cambiando le modalità di consumo degli utenti italiani?

La diffusione di Netflix ai livelli già raggiunti negli USA o in UK vedrà forma in Italia solo molto gradualmente. Non siamo un paese dalle forti discontinuità; al contrario il sistema ed i consumatori finali si caratterizzano in linea di massima per grandi resistenze al cambiamento. Passare quindi da 50 anni di tv generalista (di cui 30 di duopolio) a modalità di consumo in forma di Video On Demand non è affatto banale. Infatti, sebbene varie offerte siano presenti sul nostro mercato già da diversi anni, solo il 50% della popolazione ha consapevolezza dell’esistenza del VOD, ed appena il 5% l’ha direttamente sperimentato. Ma l’americana Netflix ha dalla propria parte – oltre a consolidate capacità di marketing specifico in termini di profilazione dei clienti, reccomendation engine, promozione innovativa e user experience ottimizzata – la forza di produrre contenuti distintivi importanti e, soprattutto, la robustezza finanziaria che deriva da una capitalizzazione di mercato pari a circa 55 miliardi di dollari. In altre parole, hanno ossigeno in abbondanza per perseguire le proprie strategie anche in un mercato per molti aspetti sempre più competitivo.

Quale modello prevarrà? La scelta “alla carta” del VOD o la formula tramite abbonamento in S-VOD?

I vincoli imposti dagli esercenti cinematografici in tema di finestre di sfruttamento dei titoli dopo l’uscita in sala hanno reso il TVOD-Transaction Video On Demand finora più interessante dello SVOD in termini di “freshness” dei film proposti. Ma la formula di consumo in abbonamento (SVOD-Subscription Video On Demand, un “all you can eat” con migliaia di titoli a disposizione) è quella che – ai bassi prezzi di 5-8€/mese cui è arrivato il mercato anche da noi – sarà in grado di fare breccia nel cuore e nel portafoglio degli italiani, nonché di rappresentare una concreta alternativa al diffuso fenomeno della pirateria.

Poi, quando il pubblico diventerà più esperto, è comunque immaginabile una qualche rilevanza del cosiddetto “cherry picking” da parte dei consumatori più esigenti che si approvvigioneranno dei content di loro maggiore interesse, one by one, su varie e diverse piattaforme distributive; il TVOD, la vendita “a la carte”, continuerà quindi ad avere ancora qualche spazio.

L’affermazione del VOD/S-VOD porterà ad un superamento della visione lineare del sistema radiotelevisivo?

Il telespettatore italiano “passivo”, pantofole ai piedi e telecomando alla mano, è una realtà che resisterà ancora a lungo. Non a caso anche Sky, il principale player della pay tv, ha rivolto parte importante dei suoi investimenti alla tv lineare in chiaro (attraverso i canali Cielo, Mtv e SkyTg24 della tv digitale terrestre); dopo molto anni di presenza sul nostro mercato, non è infatti riuscita a superare la soglia dei 4-5 milioni di clienti paganti e, con l’arrivo dei nuovi player del pay, rischia di perderne una parte; un “mirror” della propria offerta premium anche su tv lineare è stato ritenuto di importanza strategica. Per gli italiani la tv è ancora un consumo di flusso, un rito collettivo; e questo è soprattutto vero per i moltissimi telespettatori anziani. Ma le giovani generazioni, i nativi digitali, sono già lontani da tale modello; abbiamo una delle più alte penetrazioni di smartphone e tablet, e la fruizione di video su web (e più in generale il tempo dedicato all’intrattenimento), per loro passa sempre più su quel tipo device.

Fonte [Huffpost]

“La prima tv rom del mondo” – di Antonello Chindemi per Internazionale -

http://www.internazionale.it/notizie/2015/07/22/rom-tv

“Cosa ho capito guardando lo speciale del TG1 sugli hipster” – di Niccolò Carradori per VICE -

http://www.vice.com/it/read/cosa-ho-capito-sugli-hipster-guardando-il-servizio-del-tg1-234

“La tv visionaria di Enzo Trapani” di Demented Burrocacao per VICE

http://www.vice.com/it/read/demented-parla-da-solo-enzo-trapani

“Ho guardato Agon Channel per 15 ore consecutive” Niccolò Carradori per VICE

http://www.vice.com/it/read/ho-guardato-agon-channel-per-15-ore-consecutive-739

The “Birdman”

With CDs, VHSs and old cassette tapes stacked to the ceiling, Rainbow Music is a hoarder’s paradise. However, its quirky owner, known as ‘The Birdman’, knows exactly where everything is. Amidst the Starbucks and Subways popping up on every corner of the East Village, Rainbow Music maintains its mom and pop feel, and is a hidden gem to its patrons. Due to the weak economy, online music sales and pirating, and the changing neighborhood, this charismatic curmudgeon is struggling to sell what he has in his store. Despite these challenges, The Birdman carries on to his own tune.